The scary thing about inflation now is not that it’s the highest it’s been in 40 years, it’s that it’s high and trending up. The last time this happened – back in the late seventies and early eighties – recessions followed. Money supply was reduced, and interest rates were raised and, as in a perfectly built chain of dominoes, the last piece to fall was aggregate demand. Consumers spent less, unemployment rose, and, as a result, inflation gradually subsided.

The last two generations of consumers (and marketers) have only read about high levels of inflation in economic literature, they haven’t had to deal with it in real life. But for the last six months, the rate of change in the prices has been hard to miss. Labour shortages and rising energy, gas and oil costs have inflated consumers’ basket of goods and shrunk businesses’ margin potential.

History teaches us that strong growth isn’t on the immediate horizon. And that’s ok.

Growth is achievable if you sort out profit first

Christensen, Harvard Business School professor and the architect of the world’s supreme authority on disruptive innovation, said that innovators should be patient for growth, but impatient for profits. As sage as this advice sounds, our world currently has a fascination with billion dollar unicorns that hastily sacrifice profitability and sustainable growth at the altar of growth at speed (think WeWork: the making and breaking of a $47 billion unicorn).

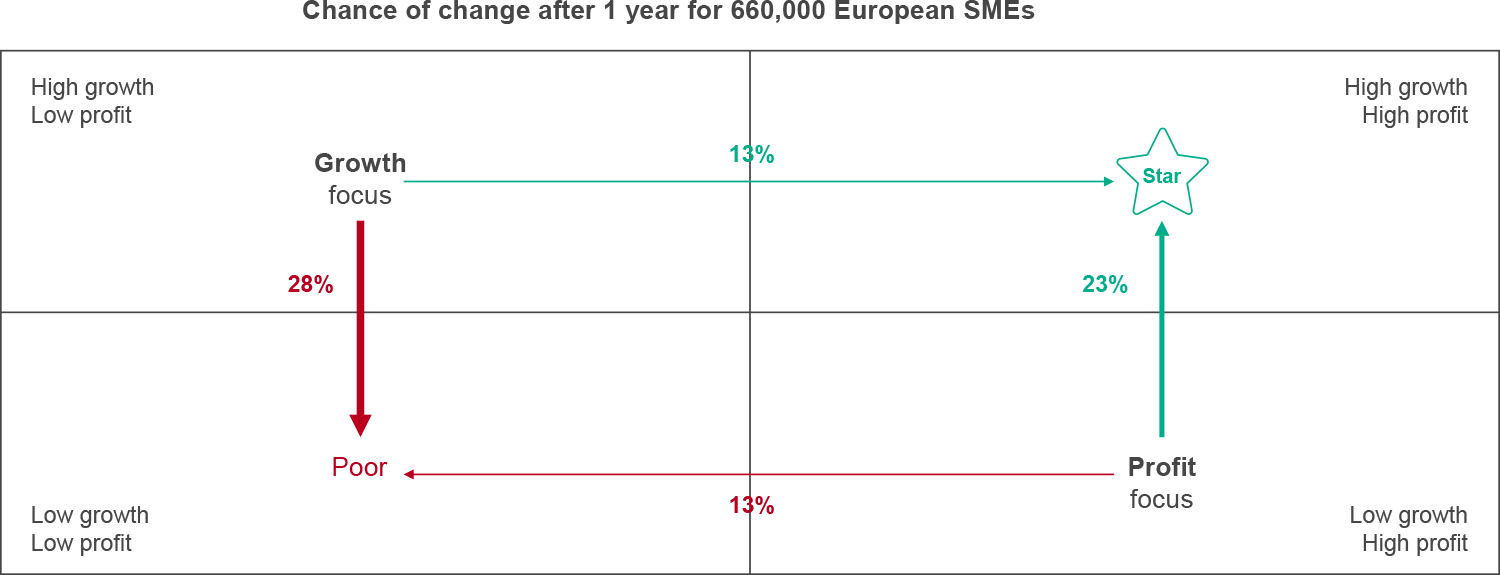

Growth at all costs might take you to the poor box. Such is the finding of a research study by Per Davidson at al. that was later replicated with greater rigour by Cyrine Ben-Hafaïedh and Anaïs Hamelin. The two academics conducted a study covering over 650k firms spanning 28 countries and a variety of different sectors and sizes. Their findings?

Firms are much more likely to end up in the enviable position of achieving high growth and high profitability if they focus on profitability first, and then expand. They also found that firms are much less likely to become profitable because of their growth.

We believe the same principles apply to brands of any size. A focus on growth alone is not enough and can even be dangerous. Brands create value through higher margins and greater profitability.

Success is more likely to start with a profit focus, not growth

Source: Analysis of 660k European SMEs | Research article

Fixing price is key to profitability

But hang on, whose job is it?

Pricing and profitability are unquestionably linked. It has been almost 20 years since McKinsey published evidence that a price increase of 1% could generate an 8% increase in operating profits. Seven years later, foremost pricing expert Rafi Mohammed revisited the question in his book 1% Windfall, in which he argued that profitability would shoot up by more than 10%. In fact, out of all the levers one can pull (including sales, fixed costs and variable costs), an increase in price will have the greatest impact on profitability. The caveat? Not many want to pull it: 3 in 4 CMOs question whether pricing is even part of their remit.

Although for some, pricing is the overlooked P of the 4Ps of marketing, a brand’s pricing power – its ability to raise prices and still influence consumers to pay without losing business to competitors – is a measure of its perceived value. Once market research is done and segmentation, targeting and positioning have taken place, it’s an opportune moment for pricing. At precisely this moment, marketers are asking: ‘does our target segment believe our product or service is good value?’ before they swiftly move on to reap the harvest of their hard work on behalf of the business.

But instead of seizing the moment, many succumb to the lures of price promotion.

Marketers often sabotage their profits

Why is that?

Although the very essence of marketing is to sell more stuff to a greater number of people at higher prices, marketers often resort to price promotions. Some of that is simply a necessary evil. Discounting is an established way to maintain or increase physical availability: being price competitive allows you to maintain retailer listings and ideally create short-term growth which opens up new line distribution opportunities.

However, you need to make sure you are managing against that objective, as perilous downsides will come from it: firstly, price promotions are often a magnate for existing customers - half of them would have bought your product anyway (at full price) and secondly, your competitors will follow suit with a similar sales promotion act. The temptation to do it again the following year just to hit your sales targets will likely land you in a price war, or a ‘spiral of doom’ cycle, and decimate your profits.

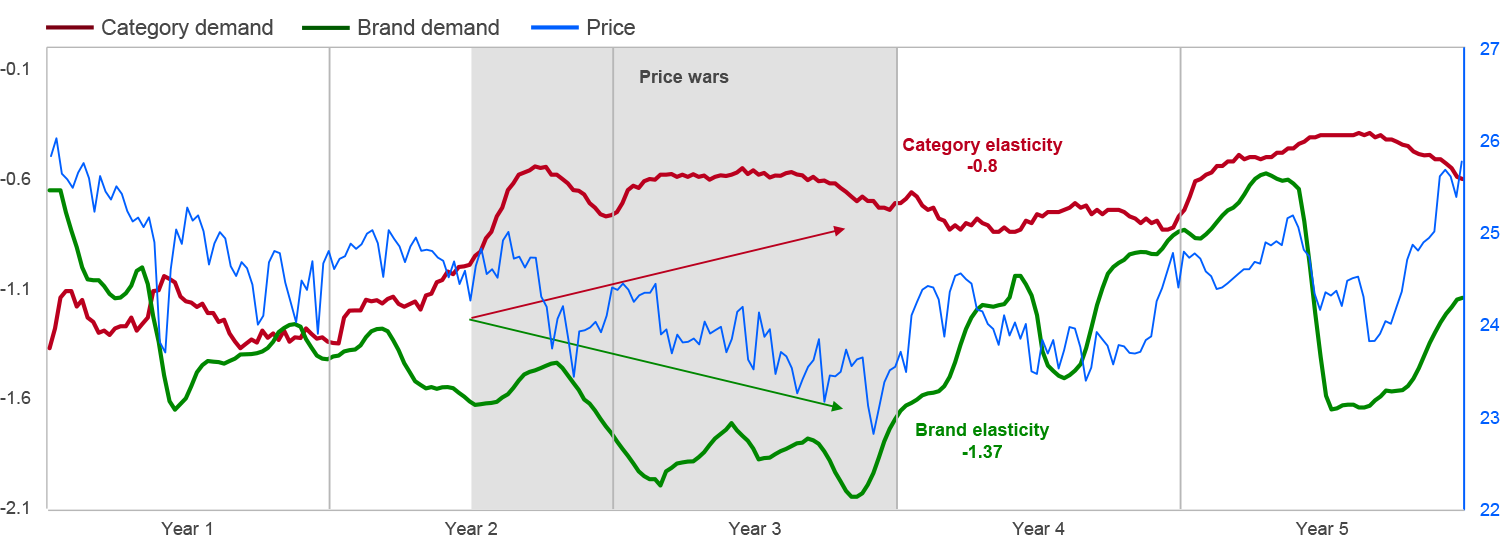

We analysed the chronicle of a price war for one of our clients, a leader in an FMCG brand in Mexico. They were determined to find out whether sales promotions are beneficial or detrimental to their portfolio and to the whole category. A key factor was price elasticity of demand – a measurement of the change in consumption of a product, brand or category in relation to its price. We found:

- A decrease of 1% in price brought relatively low incremental volume to the category, i.e., category volume is inelastic (-0.8), whereas demand for the average brand was elastic (-1.37) and resulted in lower volume and brand share.

- The price war quickly turned into a game of winning and losing share but did little good to the category and brand portfolio profits.

- A 5% decrease in price roughly resulted in a 5% increase in volume. Whereas a larger price cut of 15% resulted in a 22% increase in volume – an action that would, in all likelihood, trigger another damaging price war.

The anatomy of a price war -in the spiral of doom, the biggest loser is profitability

Source: Category and brand elasticity of demand during a price war/ FMCG, Mexico

The perils of discounting are greater for name-brand or national-brand products and services compared to private-label or store brands. Research has shown that share gains made by private-label brands during economic disruptions are asymmetrical: when the economy recovers, private-label brands retain a good portion of their share gains, however, name-brands don’t recover all the market share they lost.

Possibly the greatest tip about how to survive a price war (advice directed both at brands and retailers) is not to start it by signaling to your competitors in advance what you will do. Shoppers might be lured by a competitive price, still there are other values they seek on top of it. The reasons for choice vary by market (you can find more details in our eCommerce ON booklet) with product assortment, product quality, membership rewards, points programmes, ratings and reviews ranking highly internationally.

Evaluating your pricing position and Pricing Power is the most important thing to do right now

A brand’s greatest strength is its ability to justify its price – its Pricing Power – and should be seen as the first line of defense against rising prices and inflation. Indeed, billionaire Warren Buffet rates his investment opportunities on their Pricing Power, so you know that “you’ve got a very good business”.

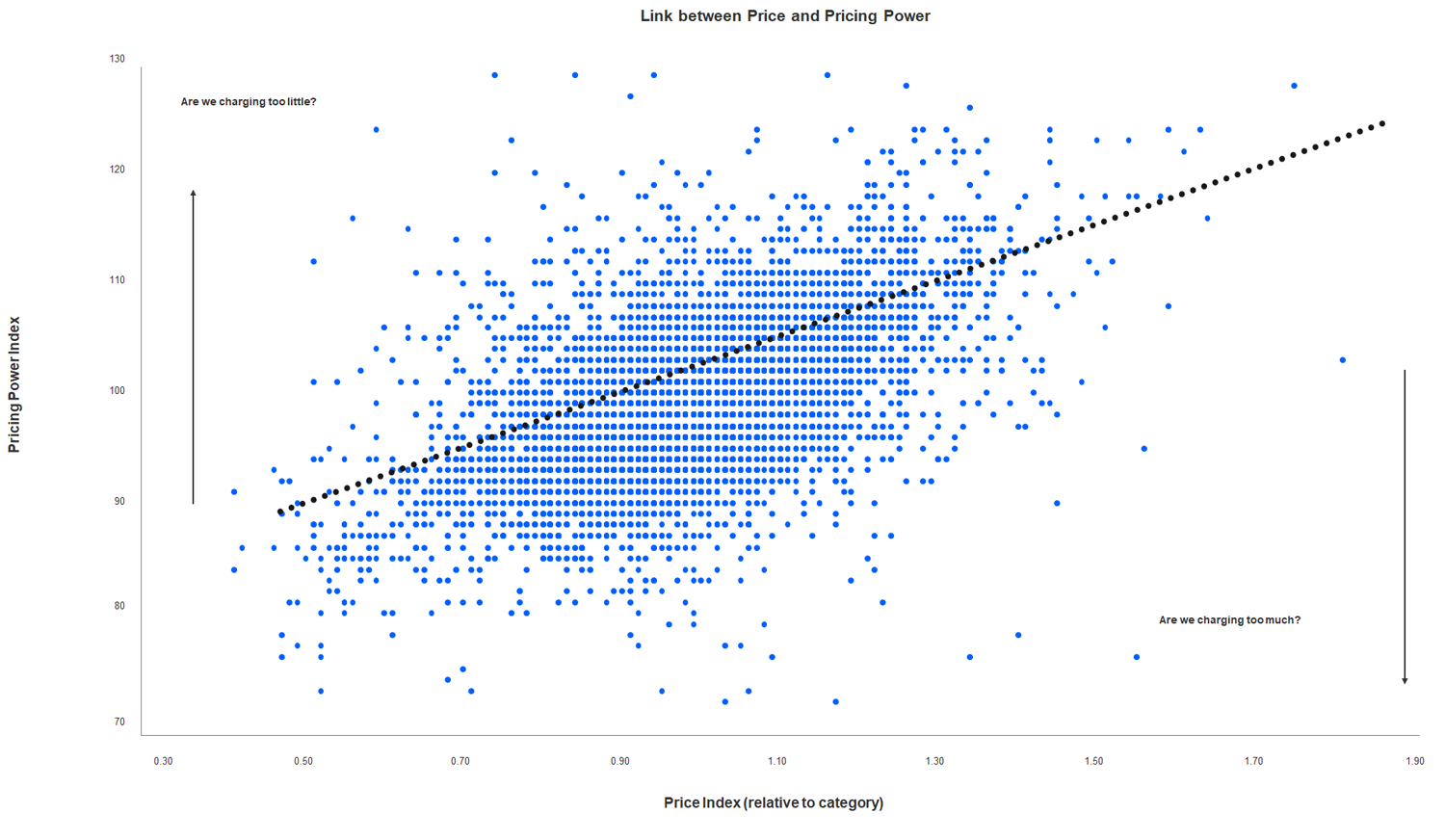

At Kantar, we have a process for assessing perceived worth relative to price. It tells you directly how to make pricing decisions and how to prepare for inflation. This measure of worth, a metric from our validated Meaningfully Different framework, is called ‘Pricing Power’. It gives marketers the courage to resist the temptation of price discounting as a knee-jerk response to inflation.

Mapping the brand equity of thousands of global brands in our Kantar BrandZ database against their current price has enabled us to quantify Pricing Power’s benefits:

- For every 4 points of increase in relative price, 1 point of Pricing Power is needed to justify it

- Consumers are willing to pay double for brands that have high Pricing Power compared with those lacking it.

We have found many of the brands analysed were in vulnerable positions as their Brand Equity does not support their current price. Is your brand well-placed on the map to defend its price, maybe even capture more profits from each sale?

The answer rests with your place against the dotted black line in the chart below. The further away you are from the line, the greater the opportunity to re-think your pricing strategy. If your brand sits north of the line, there is likely an opportunity to increase price and, equally, to ease promotional discounting. If your brand is south, it suggests that consumers’ price perceptions do not currently align with real price. This means you may have to advertise more than competitors or accept a reduced margin in the market.

Reformat your territory around pricing

Source: Kantar BrandZ

How brands achieve high Pricing Power

Three examples from our Kantar BrandZ data:

1. Loxonim S, an over-the-counter painkiller in Japan, Pricing Power Index: 114

This category uniquely has three key players, but only one can demand a high Pricing Power - Loxonim S. Consumers’ perceptions of superior performance and its personality associations with ‘expert’ and ‘sage’ archetypes reinforce its sense of difference and ability to justify a higher price.

2. Method detergent in the USA, Pricing Power Index: 107

Back in 2016, Method was a small brand with a strong potential for future growth. As more people began to use it and better understand its benefits, its high price point was considered reasonable.

3. Hypermarket/supermarket chain Kaufland in Germany, Pricing Power Index: 108

Kaufland might be a bargain store, but its prices range well above those in Aldi and Lidl. The location of its stores, the shopping experience, and the range of goods on offer explain its strong Pricing Power relative to the category.

Torn between different scenarios of your brand’s perception change? Our mind to sales simulator can predict the likely change in your brand equity and Pricing Power.

Consumer decision is richer and more complex than price alone

Consumer data is key when it comes to fighting inflation. During the 2008-2009 crisis, our Europanel data on Food and Grocery revealed that consumers were absorbing 75% of the inflationary impact. Meaning that for two-thirds of the prices, they shrugged their shoulders and pursued with their purchase.

And now again we observe the same pattern. It’s not that shoppers are happy with higher prices. But we find no proof that price has taken over consumers’ decision-making, whether it’s choosing the brands that they buy or the focus on sustainable practices. Quality, habit, and convenience rank highly as drivers of choice. Further down the pecking order, price-triggered choice was recorded as low as 11% during our first wave of the Kantar’s Global Issues Barometer.

The reality is that some brands navigate the inflation waters more gracefully, aided by the lightweight but sturdy paddles of their Pricing Power. These brands are more inelastic than others; their demand doesn’t go down when they increase price, a phenomenon we call in economics ‘price elasticity. But in simpler, everyday terms, pricing is just a muscle that we shouldn’t neglect building, more so in prolonged inflationary conditions. As this muscle gets stronger, it yields healthier margins and better-shaped profits.

“Pricing is back on the agenda big time” Mark Ritson told me in our recent Future Proof podcast. “You’ve got to make profit otherwise you won’t survive; failure will no longer be forgiven.” For that, understanding your Pricing Power and how to handle price increases become critical, especially as we might have to do it a few times. Not sure how? Get in touch to find out how Kantar can help you get there.

This article on Pricing Power is the fourth in our Modern Marketing Dilemmas series, where we discuss themes that have polarised our industry. Our POV is backed up with empirical data and is brought to life with Kantar BrandZ case studies

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay tuned for the next article of the series where we will tackle the dynamics around loyalty and whether they change in an economic crisis.